A Day on the Volta - River Tour and Akosombo Dam

|

| Denoons on the Volta |

I told the observant staff member that we had hoped to have a boat tour, but that we needed to be able to eat breakfast early and get on the road immediately, to our next destination. He then suggested that we combine breakfast with the boat tour. So, how could we say no! We packed our things on Sunday night and rolled our baggage out to the Reception Desk by 7:45. We skipped the coffee machine so that we could get underway by 8... and we were.

The pilot of the catamaran and the manager seated us and wedged a table between us with three English breakfasts, fruit, three liter-size bottles of Bel Aqua (the local drinking water), and a tea service equipped with many packets of coffee.

Next, Amos was properly introduced. He would be our pilot. He was a native of Sogakope and had grown up on the river. He appeared to be about 60 or 70 years old. If he wasn't, then his knowledge of the river and the state of the local environment downstream from the Akosombo Dam must have been gained from the lore of those who were that age and older. Once we were out in the river and a mile or two south of the Spa, Amos cut the engine, stood from his seat at the wheel, and offered us a natural history of the Volta.

It is not certain, he said, how the Volta River got its name. The word volta in Portuguese means "twist" or "turn." But most think that, in this case, "turn" is actually "return," since the Volta provided the only navigable way to or from the trading posts and villages that provisioned the Portuguese merchant ships in the days when the Portuguese were the primary Europeans in West Africa. It is fed by three major tributaries - the White, Red, and Black Volta rivers. The headwaters of all three are in Burkina Faso (formerly called, Upper Volta);

|

| A floating island of seaweed makes its way downstream |

|

| Gwen enjoys a piece of fruit near the expanse of the Lower Volta Bridge at Sogakope |

This bleak natural history at an end, Amos resumed his seat at the helm, piloted us past "the longest bridge in Ghana," turned us around, and headed us back to the Holy Trinity. Despite this sad testimony, we had to admit that this was nevertheless a lovely day and that the sights and sounds around us were fascinating.

Gershon was waiting for us when we came ashore and, after having a good laugh when the hospitality manager offered hospitality to the Spa's flock of ducks, again in the form of a large loaf of white bread, he spirited us away to Evans and the waiting van already loaded.

|

| The Holy Trinity Spa from out in the Volta |

|

| Ducks enjoying their breakfast |

Three hours later, we were upriver enjoying lunch at the Volta Hotel on a bluff in full view of Akosombo Dam.

This would set the scene for the next portion of our day - a tour of the very dam Amos had been damning, that morning.

After lunch, Evans drove us to the offices of the Volta River Authority (VRA). The VRA is an independent company established by the government of Ghana for the purpose of administering the Akosombo Dam (and other energy projects throughout the country). It was established in 1961, when the dam project was in its early stages, and has a multiplicity of roles. One of those is the oversight of the population displaced by the creation of Lake Volta on the north side of the dam. Social workers are therefore a primary human resource of the VRA, and one of them - Kweku - provided us a tour of the dam. - see FOOTNOTE ON NAMES, below -

Kweku told us that Akosombo Dam was one of a number of water-powered projects along the rivers Volta conceived in the early 20th Century by the geologist and naturalist Sir Albert Kitson who had just previously also discovered bauxite deposits in the region and imagined that the dam could be used to power an aluminum smelter. Interest in such a project was invigorated during the 1940s when Kitson's notes were rediscovered by the Gold Coast government, Ghana's British colonial administration. Just after independence, Ghana's first president Kwami Nkrumah discussed with our own President Eisenhower the potential for an American aluminum company to work with Ghana to fulfill Sir Albert's imagining. The company Kaiser Aluminum was eventually recruited, forming a new company, Valco, which built the smelter at Tema. When the turbines began turning in 1965, eighty percent of the power was directed at the smelter. The remaining twenty percent was distributed through high tension wires across southern Ghana, Togo, and Benin. Ghana's portion provides about sixty percent of the electric power required by the country.

Kweku told us all this, while seated beside me in our van. The rainy season of Ghana was having its way. There was a gentle but persistent downpour, and we decided to wait it out before touring the top of the dam - a road across which light vehicles and maintenance equipment could travel with ease but which we had to traverse on foot. About twenty minutes later, the steady rain became a sprinkle, and we proceeded out, to see this wonder of engineering.

Sir Albert Kitson had recognized that the steep and narrow gorge formed by the river at Akosombo, if dammed, could harness the power needed to industrialize the Gold Coast. Some enterprising Italian contractors recognized that this could be achieved cost effectively and simply by filling the river's channel with rubble blasted from the walls of the gorge.

The power plant includes six turbines that when combined can generate as much as 1,020 megawatts of electricity. Customarily, only two or three are online at any given time, to allow for maintenance on the others. Kweku noted that low water levels may sometimes limit output and observed further that global climate change, including diminished rainfall in West Africa, has contributed to this decrease.

I wondered at this, since Amos that morning had indicated that high water levels on Lake Volta were what had triggered approximately annual spills into the lower Volta and had frequently ruined villages downstream. Kweku responded that the last massive spill had happened after an unusually heavy rainy season in 2010, followed by the highest Lake Volta water levels ever recorded. This had done some harm especially to the villages where displaced people had relocated - a painful irony, since they had been moved to their new settlements in order to avoid the flooding above the dam. But the VRA, he insisted, was on the job, and the spills since had all been done in a carefully controlled fashion, to avoid the kind of hardship that was created in 2010.

Kweku told us that his primary job as a social worker with the VRA was to help people get the best educations they could. Because most of those displaced had been farmers or fishers, and the economy was already (shall we say) awash downriver with people who were similarly employed, virtually all the inhabitants of the upriver towns now had to be trained for new fields of work... or else placed on the government dole. The latter had been mostly the case for the generation immediately affected, but now their descendants are growing up in crushing poverty. (According to the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 2010 the mean annual household income in Accra was $950, while the median income was $730.) - see FOOTNOTE ON POVERTY IN GHANA, below -

As we walked the road across the top of the dam, Kweku pointed out a number of things visible from our position. There was Peduase Lodge, a presidential retreat built on the mountain that was facing us in 1959 for Osagyefo Dr. Kwasi Nkrumah - isolated and accessible only by a military road or by helicopter. Peduase Lodge fell into disrepair with disuse during times when reform was the central focus of government, but in 2001 it came to be recognized again as a potential resource for diplomacy (as it had been in 1967 the site of negotiations to end the Biafran War in Nigeria) and as a safe retreat for Presidents and their staffs. Kweku said that he very occasionally sees the presidential helicopter alighting there and knows "the eagle is in his nest."

There was a bright yellow pier jutting out from Dodi Island just north of us. It was emptied about five years ago of its pleasure boat, the Dodi Princess, which would cruise Lake Volta full of tourists and party-goers. Sadly, the boat caught fire while docked and had to be towed away for repairs. All the Ghanaians in our group spoke of their high hopes for its return soon.

After our tour, we returned Kweku to his office and continued on our journey, to Hohoe - our host Gershon's hometown - where he would be united with his bride Pamela and we would be introduced to her, and the Kikis Court Hotel would our next home away from home.

FOOTNOTE ON NAMES

In some countries, the practice is often to name your children according to birth order (Primo, Secondo, etc.). In Ghana the practice is to give your children names that you wish to name them, but more often than not everyone calls them according to the day of the week on which they were born. Thus, our VRA tour guide Kweku we knew had been born on a Wednesday. The first president of Ghana had been born on a Saturday, because he was called Kwame. Born on a Monday, I was sometimes called Kojo and Gwen, who is also a Monday birth, the feminine Jojo. Here is a helpful list of names, according to days of the week:

FOOTNOTE ON POVERTY IN GHANA

A bit more about the intractability of poverty in Ghana: Ghana's economy has not exactly skyrocketed since the completion of Akosombo Dam 1965. Instead, this first constitutional democracy in the movement of sub-Saharan African independence has been repeatedly thwarted at almost every turn toward post-colonial success, despite their corner on the market for electricity. (Indeed, in the most recent presidential election (December 2016), the incumbent John Dramani Mahama was defeated by Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, in part because of a series of blackouts that struck the Ghanaian power grid in 2015 and 2016. In response, a Turkish-owned temporary generator for the sake of keeping the aluminum smelter online was set up on a barge in Tema harbor, at the government's expense.)

President Nkrumah was unseated in a 1966 military coup, and the resulting government was propped up by Western powers bent on profiting as much as they could from the country's raw materials and natural resources, like the bauxite, manganese, and diamonds Kitson had discovered but also the gold, tropical fruits, exotic animals, cocoa, coffee, and sugar for which Ghana was already famously exploited. The corruption in government grew to such an extent that only a reform-minded military officer could have hoped to overthrow it, and Jerry Rawlings did exactly that in 1981. But Rawlings has repeated, in and out of office, the lament that Western industrial countries have consistently through economic isolation prevented Ghana (and the rest of West Africa) from developing profitable working economies of their own.

African countries may sell raw materials, President Rawlings has noted, but these sales are at prices the Western companies set. And when manufactured goods made of those same raw materials (fabric, appliances, automobiles, canned goods, and so on) are sold to Africa, they come at steep prices associated with the labor and other manufacturing costs of the West.

Between Africa's precipitously low wages and cost of materials and the contrastingly inflated prices associated with manufactured goods they must buy if they expect to go from place to place, communicate electronically, or even just to wear clothes, the people of these countries which make possible the rest of the world's useful goods are crippled in their household finances and their governments hobbled and their economies left in ruins.

Then, any corresponding step Africans may take to remedy the situation (for example, restructuring their systems of government and consolidating or centralizing economic power through the nationalization of commodity production), President Rawlings continues, is interpreted by Western governments as totalitarian or communistic and therefore anathema to democracy or capitalism. Cries of corruption are lodged and African states are destabilized by globalist corporations, and truly corrupt politicians or military leaders are ushered back into power for the sake of maintaining stability of Western businesses.

|

| Akosombo Dam with Lake Volta beyond it |

|

| The road atop the dam is built on the rubble that is the primary component of the dam structure. |

Sir Albert Kitson had recognized that the steep and narrow gorge formed by the river at Akosombo, if dammed, could harness the power needed to industrialize the Gold Coast. Some enterprising Italian contractors recognized that this could be achieved cost effectively and simply by filling the river's channel with rubble blasted from the walls of the gorge.

|

| Water intakes are visibly active at two of the generating stations. |

I wondered at this, since Amos that morning had indicated that high water levels on Lake Volta were what had triggered approximately annual spills into the lower Volta and had frequently ruined villages downstream. Kweku responded that the last massive spill had happened after an unusually heavy rainy season in 2010, followed by the highest Lake Volta water levels ever recorded. This had done some harm especially to the villages where displaced people had relocated - a painful irony, since they had been moved to their new settlements in order to avoid the flooding above the dam. But the VRA, he insisted, was on the job, and the spills since had all been done in a carefully controlled fashion, to avoid the kind of hardship that was created in 2010.

Kweku told us that his primary job as a social worker with the VRA was to help people get the best educations they could. Because most of those displaced had been farmers or fishers, and the economy was already (shall we say) awash downriver with people who were similarly employed, virtually all the inhabitants of the upriver towns now had to be trained for new fields of work... or else placed on the government dole. The latter had been mostly the case for the generation immediately affected, but now their descendants are growing up in crushing poverty. (According to the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene in 2010 the mean annual household income in Accra was $950, while the median income was $730.) - see FOOTNOTE ON POVERTY IN GHANA, below -

.jpg) |

| Osagyefo Dr. Kwasi Nkrumah |

There was a bright yellow pier jutting out from Dodi Island just north of us. It was emptied about five years ago of its pleasure boat, the Dodi Princess, which would cruise Lake Volta full of tourists and party-goers. Sadly, the boat caught fire while docked and had to be towed away for repairs. All the Ghanaians in our group spoke of their high hopes for its return soon.

After our tour, we returned Kweku to his office and continued on our journey, to Hohoe - our host Gershon's hometown - where he would be united with his bride Pamela and we would be introduced to her, and the Kikis Court Hotel would our next home away from home.

FOOTNOTE ON NAMES

In some countries, the practice is often to name your children according to birth order (Primo, Secondo, etc.). In Ghana the practice is to give your children names that you wish to name them, but more often than not everyone calls them according to the day of the week on which they were born. Thus, our VRA tour guide Kweku we knew had been born on a Wednesday. The first president of Ghana had been born on a Saturday, because he was called Kwame. Born on a Monday, I was sometimes called Kojo and Gwen, who is also a Monday birth, the feminine Jojo. Here is a helpful list of names, according to days of the week:

Sunday: Akwasi, Kwasi, Kwesi, Akwesi, Sisi, Kacely, Kosi. Monday: Kojo, Kwadwo, Jojo, Joojo, Kujoe. Tuesday: Kwabena, Kobe, Kobi, Ebo, Kabelah, Komla, Kwabela. Wednesday: Kwaku, Abeiku, Kuuku, Kweku. Thursday: Yaw, Ekow. Friday: Kofi, Fifi, Fiifi, Yoofi. Saturday: Kwame, Kwamena, Kwamina

FOOTNOTE ON POVERTY IN GHANA

A bit more about the intractability of poverty in Ghana: Ghana's economy has not exactly skyrocketed since the completion of Akosombo Dam 1965. Instead, this first constitutional democracy in the movement of sub-Saharan African independence has been repeatedly thwarted at almost every turn toward post-colonial success, despite their corner on the market for electricity. (Indeed, in the most recent presidential election (December 2016), the incumbent John Dramani Mahama was defeated by Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo, in part because of a series of blackouts that struck the Ghanaian power grid in 2015 and 2016. In response, a Turkish-owned temporary generator for the sake of keeping the aluminum smelter online was set up on a barge in Tema harbor, at the government's expense.)

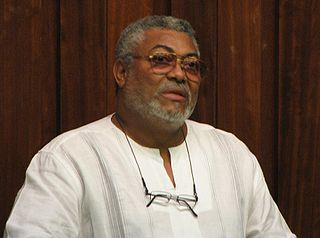

President Nkrumah was unseated in a 1966 military coup, and the resulting government was propped up by Western powers bent on profiting as much as they could from the country's raw materials and natural resources, like the bauxite, manganese, and diamonds Kitson had discovered but also the gold, tropical fruits, exotic animals, cocoa, coffee, and sugar for which Ghana was already famously exploited. The corruption in government grew to such an extent that only a reform-minded military officer could have hoped to overthrow it, and Jerry Rawlings did exactly that in 1981. But Rawlings has repeated, in and out of office, the lament that Western industrial countries have consistently through economic isolation prevented Ghana (and the rest of West Africa) from developing profitable working economies of their own.

|

| Jerry Rawlings, President of Ghana, 1981-2001 |

Between Africa's precipitously low wages and cost of materials and the contrastingly inflated prices associated with manufactured goods they must buy if they expect to go from place to place, communicate electronically, or even just to wear clothes, the people of these countries which make possible the rest of the world's useful goods are crippled in their household finances and their governments hobbled and their economies left in ruins.

Then, any corresponding step Africans may take to remedy the situation (for example, restructuring their systems of government and consolidating or centralizing economic power through the nationalization of commodity production), President Rawlings continues, is interpreted by Western governments as totalitarian or communistic and therefore anathema to democracy or capitalism. Cries of corruption are lodged and African states are destabilized by globalist corporations, and truly corrupt politicians or military leaders are ushered back into power for the sake of maintaining stability of Western businesses.