Scriptures

Micah 6:1-8; Matthew 5:1-12

When I named this message, I called it, “Balancing

Act,” because I was thinking about today being our Heritage Sunday,

and about the temptation I find myself answering when I’m doing genealogical

research or just thinking about my grandparents and great-grandparents, to feel purely nostalgic.

It’s not as though things were better, back then,

and the problem also isn’t balancing nostalgia with hope. So, what I’m going to

say may not have a whole lot to do with that title. (As my friend the Rev. Janice

Barnes

has told me, the title you give to a sermon in advance is often a placeholder

until you can get an actual message together.)

To begin, I want to acknowledge, this morning, that

we are a violent people in a violent society wrapped up in a violent world. And

I want to say what I believe: that this need not be the condition in which we

must, or our children must, or our descendants beyond our children and their

loved ones must, live. We live in a violent world, but this world need not

remain this way.

It is also simply and plainly true that, to prevent

such violence, we will have to get to work. And hard work! Work that infringes

upon our comfort, our daily comfort.

Friday, the Memphis Police Department released

video of the lethal beating of Tyre Nichols by police officers and the evident

compliance of other first responders with the brutality of those officers.

Media have played back audio and video of the incident, and it is difficult to

argue with the insistence of many Americans that the culture of policing in the

United States must be fundamentally changed, so that incidents like this no

longer occur. Yes, we have some hard work before us.

Last Sunday, I mentioned two incidents in

California of gun violence against multiple people celebrating the Lunar New

Year, and yesterday in Los Angeles there was another such incident. In just the

first three weeks of 2023 there were 40 mass shootings (shootings in which at

least 4 people were shot). Also, an average of 110 Americans die each day

because of gun violence. We and all the people of this planet must come to

believe genuinely that we cannot successfully solve our problems through force

of arms.

No one has said this clearly enough: You do not win by force of arms. You subdue, perhaps, or you

tyrannize, or you terrorize. But you do not win. Haiti is besieged from within

by gangs. In Myanmar the government outlaws voices of freedom, but those same

freedom voices when in power persecuted the Rohingya ethnic group. Holocaust

Remembrance Day was this past week, recalling the state-sponsored murder in

German-occupied territories of 6 million Jews and Roma and LGBT people during

World War II; and somehow, anti-Semitic hate and racism and homophobia and

transphobia are on the rise.

And Russia remains intent upon taking over Ukraine.

So you see… This is going to be hard work.

Where shall we begin? Because, you know the problem

isn’t just angry people or fearful people or people who will take unfair

advantage. There are also problems like poverty and disenfranchisement which so contribute to conditions of violence that they may be identified with violence themselves.

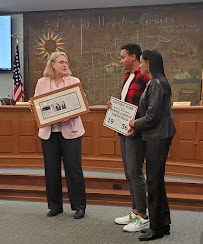

There is a movement among people of faith in

Webster Groves not just to ignore red-lining and racial covenants anymore but to

get actual legislation passed stating that discrimination is illegal. In

Evanston, Illinois, a city in which I served two different churches and

attended another, programs are being created and administered today for the

sake of restorative justice (call it, reparations) for

people of African descent who experienced Jim Crow laws between 1919 and 1969.

This justice is available to their descendants if they themselves are no longer living. The

City government is funding this municipal initiative through a marijuana sales

tax, but there is also an initiative of the Evanston Interfaith Action Council

in which churches and synagogues are committing major portions of their

endowments, or just making commitments, to a central fund being administered by

Black Evanstonians.

Poverty is violence, and economic development can

mean healing and restoration.

What does our God require of us?

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be

called children of God.”

What does our God require of us? Where should we

begin?

Dare I say, we ought to begin by remembering.

Ancient Europeans believed that memory resides in the heart. We’ve put it in the head, but I want to ponder with you

for a moment the possibility that your memory is heart-centered. Just rest in

that idea for a moment: that the same place prayer comes from, the same place

that healing comes from, the same place that will identify for you whether or

not you feel whole, is the place where your memories live.

I’m not saying that this is the perfect way to

address our problems, but I want to put you in your hearts. I mean, most of us

have at least some European blood in us, however it got there, so why not take

advantage of that perspective. You know the saying that goes with this: “Home

is where the heart is…”

Now, while

you’re contemplating that, let me take you a little south from Europe, to a

place where people actually have a saying about the importance of remembering

in order that we may imagine a generative and productive future. The Akan

people of what is now Ghana in West Africa have a concept – sankofa – which is depicted on the cover of this morning’s

bulletin. As Cliff Aerie

explained in his August edition of last year’s Jazz for the Journey series, sankofa means, “look to the past to inform the future.”

This is symbolized by a bird, sometimes flying and looking back over its

shoulder. In our depiction, the bird has reached back to take up its egg which

will become a new life.

You have to see what’s behind you, in order to

decide your most positive direction. Sankofa.

There is so much about Christian faith, and the

Jewish faith before it, and the Islamic faith as well, that is centered in

remembering. Our major holidays are rooted in studying memories – Passover,

Holy Week, Ramadan. The past informs the future for us, by reminding us of the

faithfulness of our Creator and Sustainer, our Savior and Redeemer. The Holy

One has brought us up out of bondage and given us the word of life. And we are

thankful.

One hundred fifty-seven years we have been meeting

here in Webster Groves, as this manifestation of the Body of Christ. And

practically every year we have sat ourselves down, and we have remembered –

William Plant and the Porters and the Martlings and the Helfensteins and the

Monroes and the Studleys and the Prehns

and Jennie Davis and

the Moodys,

and Dr. Kloss who wrote Our Creed, and Edward Hart

and whoever those women were who modeled for Sylvester Annan, the stained glass

artist who created our “Sermon on the Mount” window, and Dr. Inglis and the

Obatas

and Robert Parker and

Arno Haack who led the Board of Deacons when the Obatas and Rev. Parker asked

to join the church so that this white church didn’t say no. And so many we’ve

bade farewell just since I’ve been here – Tremayne and Parker and Morley and

Patterson and Davis and so many others who helped us define who we are.

These all remind us why we are as we are.

And in the cases of the Obatas and Robert Parker and Jennie Davis Sharp, we

have come to recognize people who stood out from the main group but who called

us to stand by our principles and follow our Savior’s example of humbleness and

humility.

A few months ago, I became acquainted with another

such person – Thyra Johnson Bonds, who was a member here from 1957 when she and

her husband moved to Webster, until her death in 2005. It was up until the early 1970s that she was active, especially teaching Sunday School. Her

daughters Kassandra and Gayle were active too, right up to about 8th

Grade.

Mrs. Bonds made her mark on Webster history when

she brought suit against the City of Webster Groves. The Bonds had bought their

house – a sweet little ranch with a carport – in 1957, in a neighborhood which

was on the other side of the tracks from Tuxedo Park. Homes to the east and

south of where they built had been popping up for 20 or 30 years. The Bonds,

however, had built in the very southeast corner of a 13-acre tract of land

slated for “redevelopment.” Now, when the Bonds heard “redevelopment,” they thought

what any of us might have thought: that the houses to the north and west of

them would be rehabbed or torn down and

new houses put in their place.

You see, that 13-acre tract contained a

neighborhood about as rundown as any you might ever see in Webster Groves.

Directly across Kirkham Avenue from First Baptist Church, the homes there were

either owned or rented by low-income African American families and individuals.

Many of these homes had no indoor plumbing

(meaning that, yes, there

were still housing units in our fair city as late as the mid-1960s with

standing privies!). So, yes,

redevelopment was needed.

But the City’s idea of redevelopment, flush as it

was with new federal Community Redevelopment funds, was not the same as the

Bonds. The City’s newly formed Land Clearance for Redevelopment Commission determined to

clear out those homes, and the City Planning Commission elected to rezone that

entire 13-acre tract from “residential” to “light industrial”… well, all 13

acres, that is, except for that sweet little, brand new ranch home with a

carport.

And so, from 1964 through to the end of 1968, Mrs.

Bonds and her attorney offered objection after objection, first to the City

Council and then to whatever court would hear her, expressing her concern that

the value of her property would tank, because what she and Mr. Bonds had

imagined for themselves and their daughters – a neighborhood with actual

neighbors all around them – had been prevented. She sued, for the sake of

recapturing the value of that house.

And she lost. And then she lost on appeal. And

finally, she couldn’t get a hearing before the Missouri Supreme Court.

Now that you know about Thyra Bonds, what do you

think we might be able to do – as a city, as a church, as individuals – that

can take the reality of being Black in Webster Groves, or wherever you may

live, and empower restoration? Or is there something like this that we might be

doing, individually or together, for the sake of making safe the lives of

people of Asian descent in our country? Or of children and youth? Can we

actually enable economic development, maybe even make sure that “redevelopment” means the same thing to everyone?

And before someone goes off and says that what I’m

doing is preaching politics, remember what we read in Micah – that litany of

instances in which God (unbidden!) turned things around for Israel and then

asked, “What ought to be required of you?” And then Jesus in Matthew recited a

similar litany of vulnerable people whom God is blessing (And I do believe that

the unstated comment there from Jesus is, “God is blessing these… if only the

world would too!”). Blessed are the poor in spirit; blessed are the peacemakers;

blessed are you when you are persecuted and reviled. All of that, I want to

believe, he said because he knows how hard our work is going to be –

individually and together.

Are

we relegated to a future that resembles the past? Or shall we be able to open

our theological imaginations, our evangelistic hope, our remembering and

expectant hearts, to a new future – a true and faithful future in which we

study war and violence no more?

Amen.