READINGS

COMMENTARY: The prophet Jeremiah was convinced that the overthrow of his nation’s

government by a foreign power was no accident: it was God’s judgment. His

people, he announced as speaking for God, had chosen to ignore mercy and to

favor wealth. Their greed got them into the political mess they faced and the

historical exile they experienced, as the nation’s ruling and merchant classes

were carted off to Babylon for discipline and servitude. Six centuries later,

Jesus was able to draw parallels between Jeremiah’s humiliated government and

Jewish leaders in his own time who cooperated with the power of Rome in

occupied Galilee and Judea. Note in the Luke passage the intentional linking by

Jesus between the successful of his own time with those who were the cause of

Judah’s judgment in Jeremiah’s time. He does this by referring to the

cooperators as if their ancestors were those who were sent into exile, six

hundred years before. Indeed, the Beatitudes as spoken in the gospel according

to Luke when laid side-by-side with Jeremiah’s preaching ring very familiar.

COMMENTARY: Written

in or about the year 54 CE, what we call Paul’s first letter to the Church at

Corinth is actually the third that Paul wrote to the Corinthians. The first two

having been lost to the ages, this one offers correction to misperceptions or

misconceptions those Christians had had about their new faith. In the letter

Paul demonstrates their misapplication of what he had written before. In

this passage the misapplication has to do with the central tenet of the

Christian faith – Christ’s resurrection. Paul weaves an argument together out

of Jewish thought and Greek thought. His argument is sublimely logical, like

arguments of Plato or Aristotle, but his premise and his conclusion are like

those of the ancient rabbis. He

focuses on a predicted end-of-history event, the raising of the dead, when God

will pass judgment on all people. This resurrection will provide for the

righting of historic wrongs. It will reverse the fortunes of those who lived

unjustly but without punishment and those who lived righteously but without

mercy. Jesus’ own resurrection has been proof that the day is coming, Paul

says, and the arrival of that day is the lynchpin of Christian faith and

proclamation. This claim was as

problematic for his Corinthian audience as it may be for us today. There is no

physical evidence of Christ’s resurrection, no glorified Jesus who is visible

anymore. There is only testimony and theological imagination. Paul counters those

who claim to practice this faith without believing in a coming resurrection by

suggesting that the dubious are calling him a liar.

A sound file of this sermon may be found at soundcloud.com/FirstChurchWG

Today is the Sunday of Presidents

Day weekend. Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin were both born near this day.

Darwin and Lincoln, those two voices which have had the most defining effect

for America in our history, were born on exactly the same day – February 12,

1809.

It’s also African American History Month, and today is our special observance of Science and Technology Sunday. And even though it may seem as though we’re forcing an issue just because of the confluence of those coincidences, I still was inspired to consider that confluence. After all, all of life can seem sometimes as if it’s just a confluence of coincidences that we’re trying to make sense out of – as if the combination of circumstances in our environment are forming a vortex, and we are at the center of it, trying to imagine what all of the randomness means, like Alice in the Rabbit Hole.

Our scriptures for today seem like part of it. Jeremiah and Luke offer beatitudes and curses; Paul scolds the Corinthians (interestingly) not for not believing but for not believing enough! And, I’ll tell you, the Psalm of the day, which doesn’t appear at all in this worship service, is the first of the Psalms exalting the faithful for being like well-watered trees full with leaves. Four disjoint sayings, except that Jeremiah and the Psalm both share similar tree imagery, and Jeremiah and Luke share a similar motif of blessing and cursing.

So you can imagine, I find that reading scripture passages together can be kind of confusing and feel kind of random unless they can be considered with a certain topic. And with the timeliness of considering together both how some of our citizens have been historically mistreated (because of Black History Month and Lincoln’s birthday) and what we do with what we know (because of Science and Technology Sunday and Darwin’s birthday), I thought I might be seeing a glimmer of something meaningful shining through Paul’s remonstrance of Corinth and Jesus’ beatitudes in Luke.

Blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude you, revile you, and defame you on account of the Human One.

That’s what Jesus

said.

If the dead are not raised, then Christ has not been raised. If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have died in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied.

That’s Paul.

Those two portions really stuck out to me with their emphases of suffering and death and breaking their strangle holds on our existence. I thought, That’s where I want to go with this.

Those two portions really stuck out to me with their emphases of suffering and death and breaking their strangle holds on our existence. I thought, That’s where I want to go with this.

So, on Facebook I asked how other people

encounter Paul’s assertions in First Corinthians 15 about Jesus’ resurrection

and the coming resurrection of the righteous. Where and how have you met

(are you meeting) the Messiah? I asked. Another way to put this, I

said, might be to ask, What is real for you about your faith?

Here are some of the answers I got:

If Jesus was not physically and spiritually resurrected he is not Jesus the Christ, the Messiah! I, because of the witness of those who where there, believe in the full resurrection of Jesus. And that the promise of eternal life in Christ is real because God’s promises are real. I have a faith that says that those who die in Christ shall live again and that this spiritual place is a communal gathering of those who have also lived and died in Christ. So to answer the question, it is important because I believe in a faithful God, who has never failed, lied or not come through. I believe that there are many metaphors in the Bible, but that the bodily and spiritual resurrection was testified to by the Apostles and to their followers whom I believe to this day.

A medical professional said, There is a major difference between resurrection and resuscitation. Resuscitations occur frequently in ambulances and hospitals around the world. Jesus’ resurrection is important because it set a precedent. He was the “first fruit” and because Jesus did we have the testimony of this happening in God’s Word, we have faith that we will rise again after death too new life (and not just be resuscitated to live the same old life).

[A Japanese pastor said that she asked] for help with [her] sermon on Twitter! She asked the question, “How do you believe in the resurrection of Jesus?” and got 73 responses to her multiple choice answers. Answer 1: I believe ultimately in the resuscitation of the Jesus body – 30%. Answer 2: I believe in only idea of the resurrection of Jesus – 15%. Answer 3: Not exactly sure what happened but believe in the meaning of the resurrection of Jesus – 55%.

One church member replied, I honestly don’t have a clue about whether there was a resurrection... Jesus presented to us a way of living.

I think the bedrock fact of the resurrection is that Jesus showed up and changed people... And the bedrock meaning is that God is ultimately on Christ’s side, evidence to the contrary sometimes notwithstanding.

To me, it doesn't matter if Jesus rose bodily or in Spirit. What matters is Christ made known that he conquered death itself and that there is life beyond what we know on Earth.

Quoting an Easter sermon I preached about five or six years ago, one church member said, I think of the resurrection as “Jesus loose in the world.” It had a big impact on me and how I think about the resurrection.

I find Christ’s presence in the often surprising evidences of guidance and providence in my and other's lives. A person can be clever and far-sighted in planning one’s own life, but the way things fall into place (or don’t) outside of one’s control does create story-arcs that, to me, are amazing examples of Christ's presence.

I think about the resurrection this way: I

think that, as I’ve said at other times, If it could happen for Jesus, it

can happen for us. Resurrection, whatever it is or means, indicates the

possibility of new and glorified life in God.

We claim to have good news. We use the word gospel a lot, but it can sound mysterious. So, let me remind you that, when Paul or Jesus said the word we say when we say gospel, they said, “good news.” So, that’s what we have: good news bringing meaning and relief, salvation and life, despite the strangle holds of suffering and death. That is the meaning of resurrection.

We claim to have good news. We use the word gospel a lot, but it can sound mysterious. So, let me remind you that, when Paul or Jesus said the word we say when we say gospel, they said, “good news.” So, that’s what we have: good news bringing meaning and relief, salvation and life, despite the strangle holds of suffering and death. That is the meaning of resurrection.

Even so, even for all his concentration on our good news, Paul points out that it really is no news.

Because of the resurrection of Jesus, he says, and Christ’s glorification by God, we don’t have a Jesus with whom we can make physical contact anymore, the way the apostles once did. This can be a problem, he admits, because we may then believe in Jesus’ actual resurrection, but we may imagine that it was a one-off and that he would have been the only one who gets that treatment.

No, Paul insists, Jesus was only the first. A day is coming... and you can read about what he envisioned for the rest of us in my commentary. But people then weren’t believing it. They were coming up with rationalizations and explanations for their loved ones dying and not being raised. They were doing the things that we do: insisting that people live in our hearts long past their earthly lives, and that this is what lends them eternity. Or that their spirits are still among us, and that this is what proves their eternity.

Paul said, No, that isn’t enough.

And you and I know: Our sentiments are sweet, but they’re cold comfort.

When you think about what he saw in daily life – its cruelty, its futility, and itscrushing effects on some, while others either take for granted their affluence or didn’t take it for granted and insulated and isolated themselves from the suffering that is so often the expense of their luxury. Paul was not satisfied with some sort of “pie in the sky when you die by and by.” Paul insisted that, if there was going to be justice, it had to be real. If, therefore, resurrection happened for Jesus, it has to happen for us too.

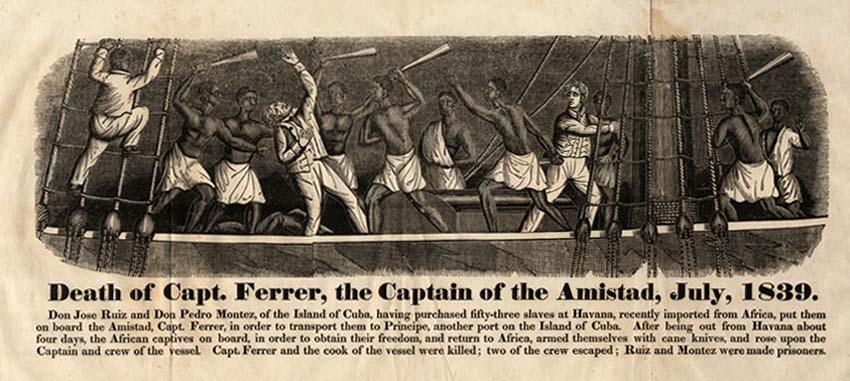

Paul, not having lived through the Dark Ages or the Enlightenment, hadn’t come to any sort of notion about democracy or anti-slavery or workers outnumbering their masters and casting off their chains. He didn’t know about such things, except that invariably, when he saw the underclasses rebelling, they were subdued and subjugated again and again.

What he knew was that there came now this good news from on high, a good news that he preached: that the Creator was redeeming the world and that, eventually, those same sufferers and their suffering children would be saved and justified, and their oppressors and all those who did nothing to ease their burdens made to suffer for the sins they committed in this life.

And even without Jesus in his former flesh restored to assert the authority and glory of God, that measure of no news, that He’s not here, still was good news for Paul and other Christians. Keep your eyes on the prize, Paul instructed the Corinthians. Accept no substitutes.

No news is good news.

This was a problematic assertion back then, and it is a problematic assertion in our own time. No news can be dangerous in a world that is growingly more disposed to evidence. The development of science in human history has led us to draw our most assured conclusions about the patterns around and among us. We do this through evidence and, in particular, measurable, quantifiable, repeatable evidence which reveals to us laws of nature and of physics which are only ever poetically referred to in scripture, if they are referred to at all.

Religion, meanwhile taking the sometimes-deadly combination of a lack of evidence (no news) and an abuse of the evidence we do have, has often faced contradiction (and continues often to face contradiction) either with force or with denial. Our refusal to submit to science’s superior knowledge has always led to exactly the suffering we are supposed to prevent.

And a share of that suffering is beginning to affect not only poor people but affluent people also. Up to now, we’ve been able to keep the world pretty well divided between the poor and the affluent (I’m not going to say rich, because most of us don’t think of ourselves as rich). We have been able to isolate ourselves from the kind of despair and misery that exists in two-thirds of the world, and maybe even more than that. We have been able, through our advances, technological and otherwise, to separate ourselves from the pain of existence that people suffer through starvation and famine, or through war and suffering, or through corruption. But now we’ve got global warming. There was a time when affluence could provide insulation from suffering, but no more. Now, we’ve really done it.

Poverty has always been accompanied by violence or destruction, but even what we might consider a small amount of affluence has provided protection from misery. Technology, even the simplest or most basic, has borne the evidence of this. The generation and widespread distribution of electricity, as well as the development of the internal combustion engine, of batteries, and the host of means of providing energy to masses of people have lifted humanity up, as far as our relative standards of living are concerned. But they have brought with them war and corruption and pollution. The advancements in medicine and hygiene, the purification of water, and the development of chemicals for use in everyday life have likewise made possible longer life expectancies. But what is the value of a longer life if violence continues and injustice persists?

Let me be clear. If you are poor, the best you can hope for in the face of violence and corruption and pollution is that you might be able just to live with it. But if you’re affluent, you have the choice of either fighting it or fleeing it. You can get away.

But the way things are today, fight or flight may not exist as an option much longer.

The rabbi Jesus and the apostle Paul call to us with the voice of the Holy Spirit, reminding us that no news is good news! We may not have physical evidence by which to prove our faith, but the truth of our faith is undergirded in a belief that the impossible for one is possible for all.

If it could happen for Jesus, it can happen for us. Resurrection, whatever it is or means, indicates the possibility of new and glorified life in God. And God did this, intervened, raised Jesus. And God will raise us too.

And whether that’s a day of justice at the end of time, or today when we presume to follow in Christ’s footsteps and seek new and glorified life in God: that’s our choice. Resurrection, whatever it is, whatever it means, indicates the possibility of new and glorified life in God.

I’ll tell you why I think this way. If there are so many who are suffering in this life, especially young lives being wasted as Pilate intended to waste Jesus’ young life as an example for others, then certainly in that way if it could happen for Jesus, it can happen for anyone.

So, it may be that our only hope is resurrection.

And here, we soar beyond the limits of what science can tell us. Here in Christianity, we soar beyond the limits of what science can tell us! From science you will only get facts and figures from which you can make premises and assumptions about future outcomes. From religion, and especially Christianity, you get promises of life and truth and beauty in love. Oh, so much love!

That’s when no news is good news, by the way... when you don’t have the slightest evidence in the world and its quantifiable, measurable results, but you have a promise, a promise you can trust. That’s when no news is good news.

And so, I don’t have the evidence to give you, to show you that Jesus was bodily resurrected and lives glorified at the right hand of God. God sort of prevented this, and yet we have that knowledge and understanding that, once it did happen. And it can happen again.

No, it will happen again.