|

| Singbe Pieh |

A sermon by the Rev. David Denoon, delivered March 3, 2013

For audio,

listen here (delivered extemporaneously).

References - Luke 13:1-9; “Black Agency, in the Amistad Uprising: Or, You’ve Taken Our Cinqué and Gone – Schindler, Morphed into John Quincy Adams, Rescues Africans — a Retrograde Film Denies Black Agency and Intelligence, Misses What Really Happened, and Returns to the Conservative Themes of the Fifties; with an Account of What Really Happened, and a Few Words about Abolitionists as Fanatics.” By Jesse Lemisch (Souls, Winter 1999); "Cinqué of the Amistad a Slave Trader? Perpetuating a Myth," by Howard Jones, Journal of American History, December 2000

The problem of suffering, Jesus seems to have said, is not really a problem. It is a condition. It is a learning opportunity... or, as a colleague of mine calls such things, "A.F.L.O." The "A" stands for, "Another," and the "L.O." refer to "Learning Opportunity." The F stands for what you think it stands for, when you are confronted with yet one more learning opportunity you don't want.

One such example of suffering might turn out to be the

Sequester, now in effect, a singularly foolish and manipulative ploy suggested by the government to convince Congress to cooperate on reducing the federal deficit. The new

recession predicted by many economists as a result could prove crippling to working people across the country.

The people of Galilee killed by Pilate didn't deserve what they got any more than the eighteen underneath the falling Tower of Siloam deserved what they got. Nor does any of us deserve what we get when life proves miserable, at least not when the disaster we experience comes as a result of anything but our own stupidity. The important part of a random disaster is not the incident itself, Jesus argues. It's the positive purpose that may come forth from it.

"They were no worse sinners than you are," he assured his listeners, "but you do deserve what they got, if you don't make things better, if you refuse the blessings of the realm of God for yourself." Such things are going to happen; that is the condition of existence. What are you going to do about it.

Consider then, a man of Sierra Leone. The title of this sermon is,

The Mystery of Singbe Pieh.

The mystery for many of you may be, purely and simply,

Who or what IS Singbe Pieh?

Singbe Pieh was the leader of the revolt that took place on the schooner,

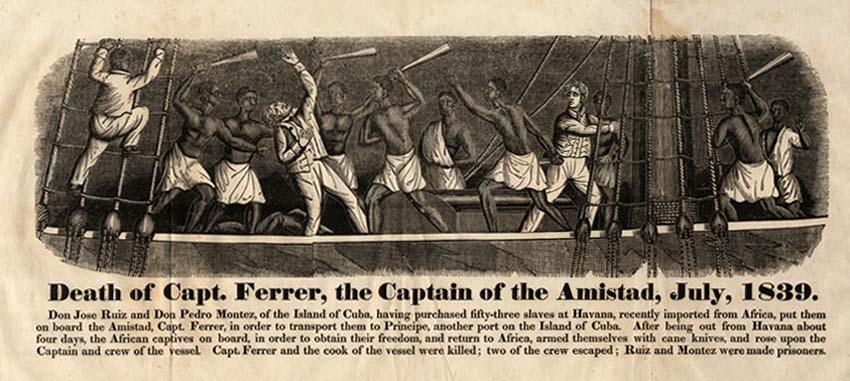

La Amistad, which was a slave ship which likely had started as a transport of human cargo between islands in the Caribbean, but which in July 1839 was captured by a U.S. Coast Guard cutter off Long Island and was subsequently brought to port in New Haven, Connecticut.

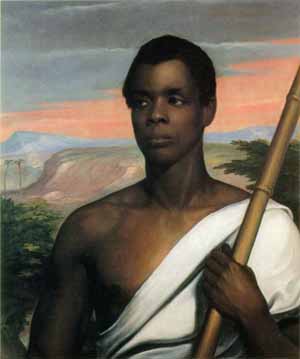

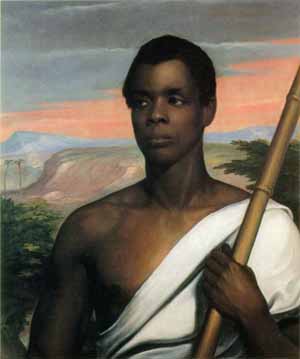

Singbe Pieh is the Mendi name of an Sierra Leonean citizen who, from the years 1839 to 1842, was known as Cinqué or Joseph Cinqué, as his case along with that of 52 other captives was considered by U.S. Federal courts and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Singbe Pieh motivated the initiation of the evangelistic effort of the Congregational Churches in America through the American Missionary Association, an association which funded not only his and his fellow captives’ legal defense but also the liberated captives’ return to Sierra Leone. (In all fairness, not only the abolitionist Congregationalists funded the legal defense and restoration of the captives, but also northern Baptist and Presbyterian abolitionists.)

For the American public who read the newspaper accounts of his capture, trial, and restoration, Singbe Pieh was either a heroic figure or a fearsome one, depending on one’s opinion of African people.

In the early 2000s, as part of the 160th anniversary of the span of years during which he and the other

Amistad captives were in the United States challenging our identity as a nation based on freedom, equality, and justice, a full-scale replica of the

Amistad funded in part by the United Church of Christ toured the seaports of the United States. In the UCC we are proud of this moment in our history.

But it is important to remember that it was only a moment, just a little over three years. Singbe Pieh’s life spanned about 25 years before the day in January 1839 when he was kidnapped and sold into slavery, and as many as 60 years afterward, depending on which account you believe.

You see, that is the problem about how we view Singbe Pieh. We treat him often as if his life began, one triumphant night in June 1839 when, after being terrorized repeatedly by the taunts of the ship’s cook about his Spanish captors’ intention eventually to butcher him and the others and sell them as food, he managed to break free of his chains and then to free others, break into a box of sugar cane swords, and attack the ship’s crew. They killed the captain... and the cook... and took the remaining crew prisoner.

That’s pretty amazing stuff. But his life included so much more that we know only shadows of. He was a husband and father of three, a rice farmer who lived in the Mendi village of Mani; so it is not difficult at all to imagine why he wanted to get back. But when he did manage to return, his wife and children were gone and the village laid waste – victims of a civil war that started while he was away. Singbe Pieh survived the Middle Passage and the American justice system. You would think he deserved a happier reward.

My new favorite author, the professor of history emeritus at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York, in 1999 published an article in the Columbia University journal, Souls, which identifies itself as “A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture and Society.” The article was entitled, “

Black Agency, in the Amistad Uprising: Or, You’ve Taken Our Cinqué and Gone – Schindler, Morphed into John Quincy Adams, Rescues Africans — a Retrograde Film Denies Black Agency and Intelligence, Misses What Really Happened, and Returns to the Conservative Themes of the Fifties; with an Account of What Really Happened, and a Few Words about Abolitionists as Fanatics.” By

Jesse Lemisch (

Souls, Winter 1999)

The

Amistad in question here is the

1997 film by Steven Spielberg starring Morgan Freeman, Djimon Hounsou, and Matthew McConnaughey (oh! And Anthony Hopkins as former president John Quincy Adams – what is it, lately, with foreign actors recruited to play American presidents!). In his article, Prof. Lemisch points out that, for all Steven Spielberg’s good intentions in creating the film which at the time the director referred to as his most important work to date, for Lemisch the film was “a present-minded Nineties screed for white paternalism.” Prof. Lemisch points out that there was a distinct lack of back story included here. Singbe Pieh appears to have come up with the idea of revolt entirely on his own. Others join him, seemingly, because he has managed to free himself and looses their chains too. There is no indication of conspiracy or planning.

But the fact that, historically, the captives used a file to cut through their shackles – not a loosened nail to unlock them, as the movie shows – they must have devised a system together to hide the file. Furthermore, their knowledge of a sealed crate filled with swords and the speed with which they must have acted to open it and distribute them – since the crew on deck appears to have been taken completely by surprise – points to quite a bit of premeditation. Lemisch argues that the real story of

La Amistad is not about a group of black people set free by the magnificent justice of a white people’s system of government or about black and white cooperation. The

Amistad incident is about resistance and rebellion; it is about, as Lemisch puts it, “black agency.”

|

| "The Revolt," one in the Amistad Mutiny series of murals (1938) by Hale Woodruff |

Not only was much of Singbe Pieh’s life stolen from him, but the moment of his triumph toward liberation is made to seem more like an accident than a well-planned victory. And yet it must have been.

Then, the most abiding story about him after his return to Sierra Leone is that he became a slave trader there. And, no matter how much evidence there may be to the contrary the allegation keeps getting repeated. The most damning evidence to the contrary is that this part of his biography is actually taken from a novel, the author of which admitted that where there were gaps in the story, he made things up. ("

Cinqué of the Amistad a Slave Trader? Perpetuating a Myth," by Howard Jones,

Journal of American History, December 2000)

Why?

Not, why would people believe this? We know that!

No, Why, after his life was so piled high with misery, would Singbe Pieh not at some point have seen some enduring happiness? At some point, hasn’t he suffered enough? At some point, haven’t we all suffered enough?

__________________________

I don’t know if it’s a satisfying response for you. I know it isn’t entirely satisfying for me, but Jesus offered this response to his followers when they pressed him to know why people who seemed innocent should have been the subject of suffering... the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mixed with their sacrifices, the eighteen who died when a tower fell on them. He said, “Were any of these less righteous than any other ordinary people trying to live life as best they could? No.”

And then he told them a parable about a garden and a fruitless tree. The owner of the tree wanted to cut it down and replace it. The one who tended the garden, however, pleaded with the owner to allow him to fertilize it. “Let me dig around it and put manure around it,” the gardener said.

That, Jesus seems to say, pretty well sums up our condition: we are given lives abounding in manure because that is what enriches them. Granted, in the moment of suffering, these words do not come as much comfort, saying as they do that suffering is inevitable and perhaps even necessary, even if in it we can find new meaning and purpose for ourselves.

People caught in disaster don’t deserve it. There's no real mystery to it. They simply were as they were when misery began. It isn’t God’s will that people suffer, and they don’t go through it or succumb to it because they are worse sinners than anyone else. The world is as it is, says Jesus: Manure happens. But because it happens, we can be better; life can be better than it was.

Singbe Pieh and his fellow captives deserve to be recognized as something more than victims of their times or as justifiers of the American system. They deserve to be seen as more than people saved from perdition by a single man (John Quincy Adams) or group of people (abolitionists). They deserve to be recognized as human beings who when they saw the opportunity to reverse their fortunes, together tried. However difficult it may be this century and three-quarters later to see them clearly, we owe them at least that much recognition. And this is the day we in the UCC celebrate Singbe Pieh and all of them and the mystery of the tragedy they shared and the life we all share. From sadness and hardship, they were able to wrest redemption into the light of day.

And their story bore brilliant fruit: Something not often remembered is that their was the first of three great slave rebellions in a period of five years. In November 1841,

nineteen slaves aboard the Creole, which was loaded with 153 slaves bound from Hamption Roads, Virginia, to New Orleans, Louisiana, overwhelmed that ship's crew and ordered them to sail for Liberia. Insufficiently provisioned for a trans-Atlantic voyage, the crew convinced the mutineers to allow them to sail for Nassau, the Bahamas, instead. Once arrived in the port of that British protectorate, despite repeated protestations from the American consulate, because British law forbade the ownership of slaves, Bahamian police set all but seven of the captives free. Those seven - three women and four children - elected instead to sail on to New Orleans.

Furthermore, in November 1842, hundreds of

slaves of Cherokees in the Indian Territory, walked away from their masters and headed for Mexico, which also had outlawed slavery.

[Here, the audio version of this sermon misrepresents the actual history. I apologize for the inaccuracy. -DD] The Cherokee Nation raised a militia which captured the slaves, just north of the Red River (Texas border). It is interesting also to note that, after this rebellion in 1842, there was not another slave rebellion until Harper's Ferry in 1859.

It can surely be no accident that, with the sensationalism of the

Amistad story in the news in both the North and the South almost constant from 1839 until 1842, that the affirmative decisions in 1841 of the Federal District Court in New Haven and the U.S. Supreme Court influenced the resolve of those slaves to assume freedom when the opportunity presented itself. Slave revolts and rebellions such as those on the

Creole and in the Indian Territory could not have occurred without conspiracy and planning of individuals convinced that freedom was within their grasp if they would only take it.

The inspiring agency of the

Amistad captives continues to bear fruit today, in articles I have cited here, and in Civil Rights and Human Rights movements, here and across the globe.

And much as the Sequester threatens to recede our economy, because we know the story of the liberated

Amistad captives, we know that there is hope. But we knew that already didn't we.

The one who told the parable of the fertilized fig tree is one who lived this reality himself. Our Jesus was arrested unjustly, and tortured, and executed for no good reason. But he would not be kept down; on the third day he was restored to life, gloriously and for ever, as a living example for us all.

We have that hope for ourselves, so let us be examples of the freedom that makes us free and the love that gives us life.

Thanks be to God. Amen.