Readings

1 Corinthians 12:1-11

John 2:1-12

I cannot hear the story of the wedding at Cana without being reminded of the critical importance of every human being, and of the riches we discover within ourselves when we are in relationship with God through Jesus Christ.

That may sound like a pretty evangelical thing to come out of my rather progressively theological mouth, but it’s true. Those six jars of water became potent wine because of their encounter with Jesus. And Jesus didn’t really want to have anything to do with them! He just messed with them because his mother basically told him he had to.

So, I don’t think that it should be unexpected that any of us would on occasion do a bit better than we had imagined we ought to be able to — given our background or upbringing or personal failings — because despite those things, we encountered the Christ.

Sometimes, God just messes with us, because somewhere along the line we said that it would be OK.

Now you may say that I’ve just blown my metaphor, because jars of water don’t have the ability to refuse what happens to them whereas people have a choice. Jesus encountered those jars, but they didn’t encounter him the way we do.

But I said before that the jars are metaphorically representing us, and every metaphor breaks down eventually.

Anyway, deal with it. You once were filled with plain old water. But now you’re filled with the best wine anyone could ever imagine, and you ought to do something with it.

To give you a sense of what’s actually possible, I want to tell you a story about a man building a church.

His name was John White.

Or maybe it wasn’t.

You see, his name wasn’t important to anybody but the people around him, back in 1845. No one wrote it down.

The souvenir program from the 100th anniversary celebration of the Rock Hill Presbyterian Church in 1945 says that his name was John. On the other hand, Henrietta Ambrose, the North Webster historian, says that his name was Tom. And indeed, the census of 1880 probably proves her right. (What the Rock Hill historian did is the definition of White Privilege, by the way. You get to rewrite history, whether you intend to or not.)

But however unsurprising it may be that history should be confused about the name of the only man (as far as I’m concerned) worth remembering from Rock Hill in 1845, it is nevertheless a pity that his name should have become mislaid in the interim.

|

| Rock Hill Presbyterian Church as it appeared not long after completion. |

You know about the Rock Hill Presbyterian Church building. It stood until early 2012 but has since disappeared. A vintner downstate claims that he purchased the stone in order to reconstruct the church on his property as a wedding chapel. But his website shows no evidence of it, in the invitation it makes to couples to stage their weddings there.

My friend Ed Johnson, an alderman for the city of Rock Hill, suspects that the stone never made it to the vineyard. And I think it would not be any surprise to discover that one white man might have miscalculated the power required to move that stone the first time by twelve black men, hewing it and hauling it and laying it.

What you may not know is why Ed thinks that a 167-year-old structure should have mattered... more than because it was a venerable, sacred space.

It’s because it was constructed by slaves.

Its stone was quarried by those same slaves.

And the labor that put a roof on that structure was donated by the team of slaves who also raised up the walls and laid the floor and perfected its interior and exterior.

After the church began to take shape, as the Rock Hill Presbyterian Church historian told it, John (or, rather, Thomas) White, the overseer of the crew, went to James Marshall, the man who presumed to own him and whose dream it had been to build the church.

[White] said that the colored members wanted to give something for the church. When Mr. Marshall told them they were giving something by building it, John replied: “No, sir, we feel that we are working for you. What we want is to give something ourselves. We thought we could put on the roof on Sundays—on our own time.” The roof was the contribution of the colored people, who felt that thus they had a special part in the building of the church.

|

| Rock Hill Presbyterian Church just before it was razed. |

For this same person who seems to excuse the slave donors by claiming that they “felt that thus they had a special part in the building of the church” (Am I wrong to infer that there is a suggestion of the phrase, “even though they didn’t” here?) is clearly humbled by a man unbent, even of a team unbent by the tasks that were being demanded of them.

The outcome of the explanation by the man whom that historian calls John White is remarkable because of the actions James Marshall appears to have taken in response, in the years following:

|

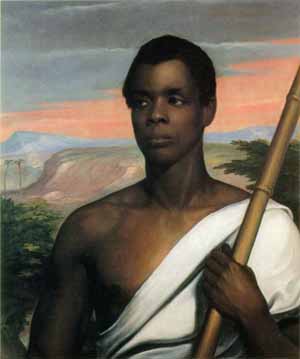

| Ed Purnell, son of John Purnell, around 1900 Mr. Purnell had also been counted among those enslaved by James Marshall. |

- Not only were the workers allowed to donate their labor on the Lord’s Day, to complete the construction of the building. They were evidently members in all but name. The writer of the history I quoted a little while ago does refer to Mr. White and the others on his team as “members.”

- They would indeed worship under that same roof at the same time on Sunday mornings as the white members. Henrietta Ambrose says that black and white worshiped together at the Rock Hill church, albeit with the bondspersons seated in the back. Nevertheless, they had seats! (And they would have them eventually in the presence of the New England Congregationalists who would come to treat Rock Hill Presbyterian as a layover for themselves until they could build a church of their own.)

- James Marshall would set free two of his slaves along with their families in 1864, shortly before his death. These were John Purnell and Caleb Townsend, whom he provided with land and aided in the construction of their homes. Thus, he relinquished all of his human assets, so that none would be passed along when he died.

- And, finally, Thomas White is listed as a 77-year-old servant in the home of Ernest Marshall in the census of 1880. Ernest was James Marshall’s son. There remained a clear commitment of family to family.

|

| The Rev. Artemus Bullard Source: Missouri History Museum |

Maybe James Marshall, as it is said of Stonewall Jackson, recognized that the practice of owning human beings was evil and simply thought it ought to be handled in a more deliberate and gradual manner than sudden emancipation.

What I cannot doubt, however, is that — on a day in late spring at the construction site of the Rock Hill Presbyterian Church — James Collier Marshall was humbled by the brilliance of another Christian insisting on the sanctity of his own dignity, impressed by the efficacy of the spiritual power of one he considered inferior, chastised by the justice of God and the truth of Christ. Thomas White went to Marshall and made him an offer that bespoke his and his co-laborers’ integrity and courage.

And lately that moment is in my mind when I hear the story of water changed to wine, and remember the variety of spiritual gifts on display when we are together in Christ’s name. Lately, that is what I think of, when I consider the riches we discover within ourselves when we are in relationship with God through Jesus Christ, even when it feels as if God is maybe just messing with us because that is what God does... gifts that deserve to be recognized and honored, cultivated and practiced... the blessed and lasting impact of the action of a man building a church.

Thanks be to God. Amen.